|

There has been a pause in the blog article posting for the past month (August 2015) due to preparation of a book chapter manuscript. The book, to be published by Routledge, is tentatively titled The Smart Cities Guidebook. The chapter I have been working on is called “Decision-making for Urban Management: Open Source Options.” Once the book is available, I’ll post details on the blog. The research process for the book yielded some interesting results I’d like to share with readers. Of course, I cannot go into the level of detail contained in the book chapter, but I’ll provide a summary in case it is useful for others working in urban management. I started out asking the following questions: 1. What are the leading edge methods for decision-making throughout the urban management process? 2. What is the so-called “urban management process”? What exactly does it entail, and who is involved? 3. What are the current and future needs for high quality urban management decision-making? 4. What are some difficulties urban management professionals encounter during the decision-making process? I’ll describe what was uncovered one question at a time, but you’ll notice that they intersect with each other. What are the leading edge methods for decision-making throughout the urban management process? I’ve experienced, heard about, and read about a wide variety of methods, but I opted to focus on one area - Open Source software (OSS) tools. After speaking and emailing with various professionals, I realized some had created/used a particular Open Source software but they were not necessarily aware of all the other tools they could also be using. More details on what OSS entails is in the book chapter, but I’ll cover two big benefits. First, the software is released at zero cost for anyone interested in using it. For urban management professionals who want to improve decision-making processes but realize there could be a hefty price tag, OSS is a great option. By bringing the cost of making high quality decisions down significantly, we enable more cities of all sizes around the world to better serve their people. After all, urban management is about making places for people that meet their needs and wants, even as needs and wants change over time. It is also important to point out that OSS does have a learning curve for most. Tasks such as getting a new instance of an OSS established for a new user, training new users on inputting data, and maintaining the OSS over a period of time do require either a) an urban management professional with this applicable set of skills or b) other staff/third party support to help in the initial phases to establish the OSS with a new user. Second, OSS is generally able to be added onto by the user community. Many of us have experienced a useful tool that seemed to be missing a key feature. With OSS, if the user has the coding skills necessary, the user can build in that feature. The user then has the option to keep the feature as their own or share with the user community, and the latter option is generally preferred to allow others to also leverage it. Chances are, someone else will appreciate the new feature and use it as well. One of the reasons why OSS is attractive to some users is this flexibility. Of course, proprietary software can sometimes be quite affordable or able to leverage plug-ins, extensions, etc., but these concepts are more foundational to OSS in general. Here is a list of the OSS tools referenced in the book chapter:

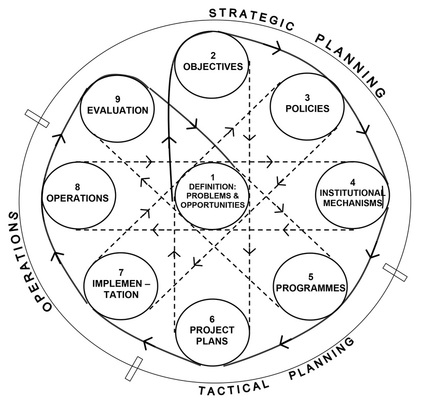

What is the so-called “urban management process”? What exactly does it entail, and who is involved? There are solid resources that clarify the steps of the process. According to Edward Leman (and I think many would agree in general), the urban management cycle includes nine steps that fall within the larger work categories of (A) strategic planning (step 1: definition of problems and opportunities, step 2: objectives), (B) tactical planning (step 3: policies, step 4: institutional mechanisms, step 5: programs, step 6: project plans), (C) operations (step 7: implementation, step 8: operations), and (D) evaluation (step 9). The image below illustrates the cyclical nature of urban management. The original article containing additional details was published in 1994 and can be accessed online. Tactics generally include, but are not limited to, infrastructure (both traditional built infrastructure and evolving technological infrastructure), services, and policy. An extremely broad range of actors is involved, and they would change depending on the step in the process. The stakeholders span private, public, and nonprofit sectors. There are those working largely in work categories ‘A’ and ‘B’ in city/urban planning functions. There are those working largely in work category ‘C’ in implementation and operational functions, such as public works or social services staff. Work category ‘D’ may coincide with aforementioned professionals or be separate staff such as monitoring and evaluation specialists. In any event, these professionals tend to have strong relationships with each other in the urban management cycle. The business/economic community and philanthropic community would have a role. The public as individuals are stakeholders, as are their representatives both non-elected and elected. I’ve created a sketch to illustrate actors/stakeholders below (certainly not exhaustive of all stakeholders to consider). What are the current and future needs for high quality urban management decision-making? I’ve referred to “high quality” urban management decision-making above. You may be wondering, what does that mean exactly? I have an understanding of what it means, but I realize the concept of anything being “high quality” is highly subjective. For me, high quality urban management requires the following: 1. Taking complexity and system interaction into account 2. Addressing the components of sustainable development 3. Structuring top-down and bottom-up processes 4. Integrating computational analytics Previous blog posts provide some background on the concepts. “The Promise of the City: Connecting the Built, Natural, and Unseen” includes some information on urban complexity and system interaction. “Complex Decision-Making: Cities, Systems, and Data” references the “three pillars of sustainable development.” I am using the term “bottom-up” in the sense of integrating needs of the public into more formal, top-down processes. Computational analytics, though not necessarily required for the other three to be successful, can simplify work to a great extent. What are some difficulties urban management professionals encounter during the decision-making process? From various processionals, I’ve heard challenges related to the previous items 1-3: taking complexity and system interaction into account, addressing the components of sustainable development, and structuring top-down and bottom-up processes. Even though many professionals would agree these concepts are important, clear methods for factoring them in are not widely available and/or utilized. While there is certainly a place for personal experience and instincts in the decision-making process, many urban issues have a great deal of intricacy. It is rare that one professional would have all the knowledge needed to understand the full impacts of the decision on the various interrelated systems and sustainable development factors, for example. There also seems to be a theme that clear communication with the actors/stakeholders listed above remains a struggle. When communicating with the public and a wide variety of professionals, vocabulary issues tend to come into play. It can also be difficult to hone a message down to its key points, explaining some complexities while also communicating in plain terms everyone can understand. Feel free to post comments below about OSS tools you have heard of or used personally! Towards a New Approach to Urban Planning: Flexibility, Decentralization and Accountability7/19/2015

In Is Urban Planning Having an Identity Crisis, written by Anthony Flint and published by City Lab on July 17, 2015, the value the urban planning field is providing in its current state was called into question by those who provide it – urban planners. The author attended a conference held by the Association of European Schools of Planning (AESOP) and wrote about his observations. Flint states, “Global urbanization carries multiple complexities, with loads of unintended consequences and unanticipated outcomes, whether in Cleveland or London or Bogota. If the future is not linear, planning in a linear fashion is the equivalent of banging one’s head against the drafting table.”

Three main ideas were woven into the article that represent gaps in the process of planning or tension between opposing approaches: 1. Flexibility in the planning process – In general, the planning profession continues to operate as if the planning process truly has control over all the elements indicated in plan documents. In reality, many projects are not able to receive funding for one reason or another. The needs for a given project change due to various circumstances. Political will might decline related to a plan component. The fact is, things change, and cities are fluid places. However, the planning profession has not adapted in such as way as to design this need for fluidity into the planning process. 2. Top-down vs. bottom-up approaches – Federal, state, and local governments sometimes try to directly enforce elements of plans with top-down authority. This generally will happen to a lesser or greater degree, especially in terms of zoning requirements. The author mentions Tactical Urbanism as a strategy for truly bottom-up planning to take place in short length of time. There is a spectrum of top-down to bottom-up approaches, and rather than an either/or solution, a mix is generally required to connect with the local context and culture while being effective in the long term. 3. Responsibility for planning decisions - The conference organizers asked the question, “Who should take responsibility for how the cities and regions are being changed?” The context around this question appears to be more prevalent public-private partnerships and work being outsourced to the private sector. That question requires taking a hard look at what is meant by responsibility. There are few international cities that actually communicate to the public what they are doing, why they are doing it, how the decisions were made, and the current progress in a clear, less technical fashion. Without this level of communication, the public cannot hold others accountable for specifics. Furthermore, the field of planning often has a highly collaborative decision-making and implementation/delivery process, therefore responsibility becomes diffused. When mistakes are made, specific professionals are generally not held accountable (nor were they in the past), regardless of the level of private sector involvement. A solution was offered in the way of the so-called “new approach.” As explained by Flint, “The new approach, so wonderfully theoretical and avante garde, incorporates understanding of complex and self-organizing systems.” Jane Jacobs’ contributions in this area were referenced. More information on her conception of urban complexity was provided in a previous article posted on May 23, 2015 titled The Promise of the City: Connecting the Built, Natural, and Unseen. While many planners would agree with the author’s views as well with the purpose of the conference, the missing link is changing how we work. We may, on one hand, agree with all of this with passion while, on the other hand, go back to work and conduct business as usual. If we want to be more effective and change our approach, we need new methods and tools to be able to plan in such a way that 1) designs for flexibility, 2) joins top-down and bottom-up approaches, and 3) increases responsibility for decision-making. We need these tools and processes to have clear purposes, be relatively easy to use, and allow for an integrated process. Life is one series of decisions after another. We make decisions for ourselves, with our families, and even on behalf of large groups of people we do not personally know, as many professions require. Decision-making authority on behalf of others is an incredible responsibility, and many professionals are tasked with such decisions each day. What is their process for understanding the scope of the decision and informing themselves with the relevant information? What will be the results of the decision, how will the results be measured, and how will the course be altered as both positive and negative results are demonstrated?

For those of us working to improve cities in the short and long term, the key to decision making is acknowledging the continually changing nature of the city. Day to day, the challenges are changing. The people are changing, moving in and moving out, remaining in place but growing within themselves personally, and that makes establishing what will work best for them a changeable element as well. Given change as an immutable fact, we act while taking into account the following: 1) comprehensiveness, 2) relevant information, and 3) collaboration. Comprehensiveness Comprehensiveness can be thought of and understood many different ways. Some resonate with the ideas behind complexity and complexity science, while others think of systems engineering or even the concept of synergy. A more colloquial way to think about it is in silos. Regardless of the degree of specialty within a profession or the narrowly stated scope of work, certain situations call for a look within, around, and between institutional, subject matter, and intellectual silos for sound decision-making. For cities, this is critical, due to their nature as a system of systems. “Synergy means behavior of integral, aggregate, whole systems unpredicted by behaviors of any of their components or subassemblies of their components taken separately from the whole” (R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking, 1975). Relevant information “Lack of knowledge concerning all the factors and the failure to include them in our integral imposes false conclusions” (R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking, 1975). When a comprehensive approach occurs, honing in on relevant information becomes the key task at hand. In this age of information, that has become even more of a challenge. One must be laser focused on the issues of primary, secondary, and tertiary importance, but how can these be established? For cities, information breaks down into two large categories: 1) technical knowledge and 2) human-centered knowledge. The former connects a variety of subject matter areas and expertise. The latter includes understanding what the residents being served struggle with day to day. One type of knowledge can never compensate for the lack of the other, and both are of equal importance. In terms of data connectivity, they must come together to influence decisions. Collaboration The more comprehensive an approach, and the more relevant information is required, the more true collaboration comes into play. Collaboration can be obvious or subtle, forced or voluntary – even physical or virtual. Take transportation issues for example. Obvious collaborators would be traffic engineers, public transit planners, and the like. Less obvious collaborators could be senior citizen centers, public school leadership, or housing real estate developers. Of course, when one thinks of transportation as enabling the entire population to make trips for a variety of purposes, these collaborators are as obvious as the engineers. After all, the leadership at a senior citizen center or a public school would be the experts in where the people live and how they are getting to their critical facility. The knowledge they have might not be technical, but it is human-centered. Likewise, some of the more obvious collaborators are informally/formally forced to cooperate by coming together to discuss funding, engineering, and schedule details, for example. Sometimes the richest collaboration is between those for which there is no mandate. These groups come together because of shared interests and mutual stakes in the outcomes. They work to build trust over time and make concessions for the larger picture when necessary. By having honest, and sometimes difficult, conversations, they realize few factors are black and white, and they find a way to meet in the middle on one initiative after another. Cast of characters Decision-making for cities involves a long cast of characters in the USA. The public, as the reason for the city, is the central focus. From this center, there are organized communities of various types, advocacy groups, and the elected officials tasked with representing the public. All of these groups represent the public in one way or another. While elected officials are one part of government, there is a great deal of technical staff to assist with decision-making. This is reflected in city-level, metro area-level/regional, state-level, and federal staff representing a host of concerns for the natural environment, built environment, social services, etc. Some examples include Housing and Urban Development, the Environmental Protection Association, the Federal Transit Administration, and Department of Health and Human Services. Not for profits/nonprofits/philanthropies provide a wealth of critical needs, as do the business community and private sector. Understanding the individual stakes of various people/groups while combining their interests with technical needs and preparation of cities for the long term is no simple task, as likely anyone who takes part in public meetings on urban planning topics can attest. Tactics, Measurement, and Adjustments After the key problems of a given city/metro area have been understood comprehensively, responsibilities between various groups for implementing tactics break down to achieve the needed results (specific solutions to problems). The tactics vary widely, but in general they include policy, law, projects, programs, and services. Some elected officials, for example, may be responsible for enacting laws and policies, but they may also have decision-making authority for funding related to projects, programs, and services. Those responsible for implementing policy, law, projects, programs, and services each have different ways that performance is measured in accordance with anticipated results. While technical staff plays a critical role, they are generally not the ones held directly accountable for decisions in the urban environment. Oftentimes, the elected officials are the ones who have the most directly accountable relationship with the public. Therefore, it is critical they have the tools and means to understand how complex issues are connected as related to their constituencies. The changeable nature of cities means the need to change course is a fact, not a possibility. When precise indicators are monitored to understand if results are met, both good and bad news will be delivered. When trying our best to understand a multitude of factors, we speculate, we guesstimate, and we make the best technical response we know. However, no one has absolutely perfect, infallible information about the situation and the people affected. For that reason, from the moment implementation begins, measurement begins. Decision makers must be prepared to adjust the implementation in the short and long term as new information comes in. Structures should allow for pivoting and making incremental adjustments – the popularity of seed funding and pilot projects indicates our quest to put a toe in the water first. Interestingly, even though decision makers and technical staff are all serving the same function, improving life in the short and long term for people, they often don’t strategize, collaborate, and act as the system they are. Policy, law, projects, programs, and services for the public often have entirely separate processes for consideration and implementation. And yet, they are often tactics working towards the same goals, for the same people, and paid for with the same taxpayer funding. Power, Incentives, and Accountability As Buckminster Fuller stated, “Now there is one outstandingly important fact regarding Spaceship Earth, and that is that no instruction book came with it” (R. Buckminster Fuller, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, 1963). Looking at all these players as a system with a variety of power types and levels, personal and professional incentives, and accountability levels can help clarify a more ideal situation for relationships. Technology-enabled solutions can play a significant role in designing and building cities with 1) comprehensiveness, 2) relevant information, and 3) collaboration. “There’s a built-in resistance to letting humanity be a success. Each one claims that their system is the best one for coping with inadequacy. We have to make them all obsolete. We need to find within technology that there is something we can do which is capable of taking care of everybody, and to demonstrate that this is so” (R. Buckminster Fuller, Norie Huddle interview, 1981). Cities are places where everything and everyone come together. They join together all walks of life in close proximity. Cities are the hope of the people who come join them. They represent opportunity in the economic sphere in terms of jobs, professional connections, and exchanging ideas. Cities also represent social opportunity related to friends, meeting a potential mate, and having roots that truly ground you to a place. In short, people come to cities for their lives to flourish.

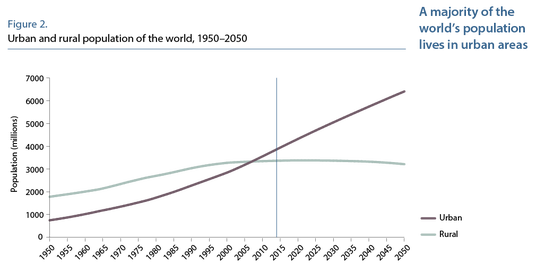

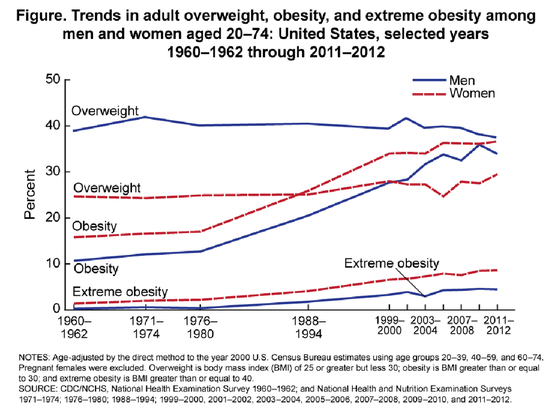

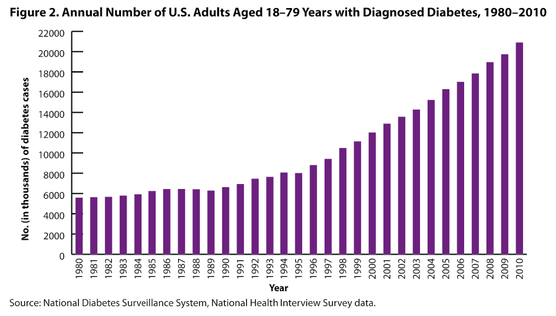

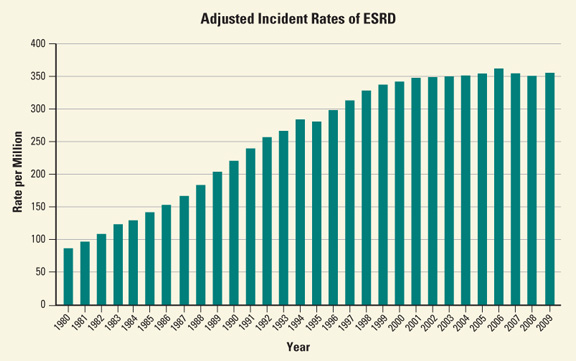

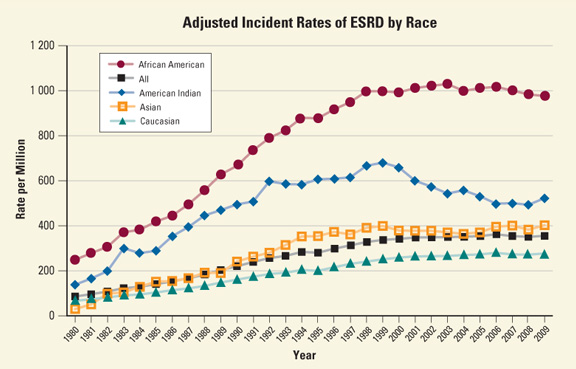

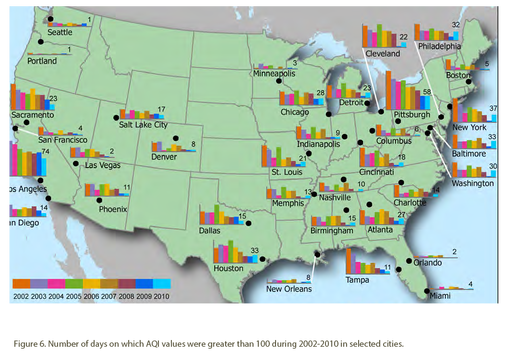

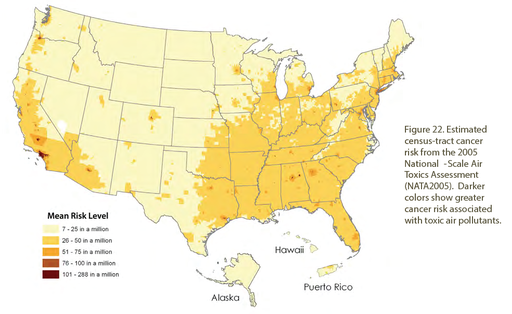

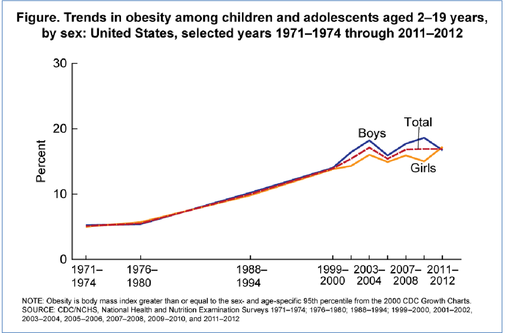

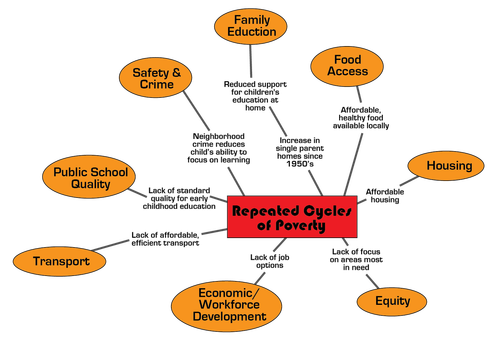

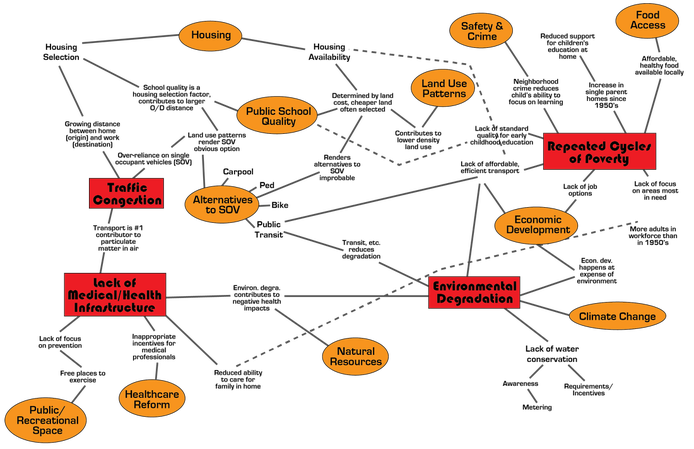

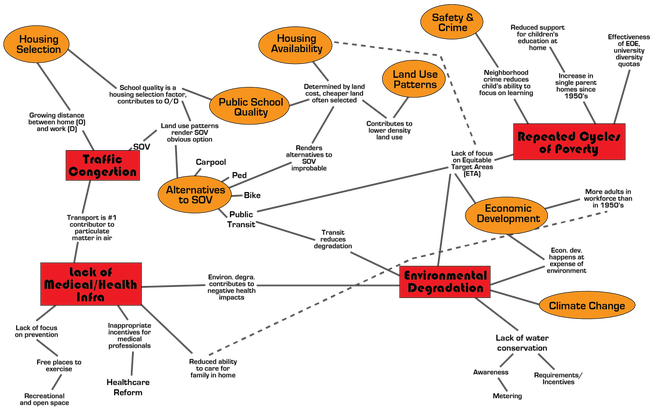

Integrating interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary understanding For people leading the planning, design, and construction of cities on behalf of the people who live in them, it is becoming more frequent that interdisciplinary and even transdisciplinary understanding is taken into consideration. Since cities function as interconnected systems, even a system of systems, those who lead urban development are working to understand its complexities. There are three primary ways that groups who lead urban development intentionally integrate this notion – through 1) individuals, 2) teams, and 3) processes. First, as individuals, professionals are becoming more "T-shaped." While they might have a very deep understanding of one specific area, they will also understand a number of other subjects/disciplines well enough to make connections between all of them. Second, on teams, there is an intentional practice of hiring people who fill skill gaps. Examples include bringing a biologist to work on an urban design team, a software developer to better understand planning functions, or a public health professional to clarify health impacts. Third, progress has been made at integrating the sustainable development “three pillars” concept of economic, environmental, and social into specific processes. Two key examples in the United States are environmental impact assessments and health impact assessments. The former is led by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The Pew Charitable Trusts describes the latter as “… a fast-growing field that helps policy makers take advantage of these opportunities by bringing together scientific data, health expertise and public input to identify the potential—and often overlooked—health effects of proposed new laws, regulations, projects and programs.” Three pillars of sustainable development The ideas behind the three pillars of sustainable development, economic, environmental, and social, were developing as early as 1987 with the publication of “Our Common Future” by the World Commission on Environment and Development (chaired by the Prime Minister of Norway at the time, Gro Harlem Brundtland). Agreeing on a common definition was, and still is, critical in order for a broad group of international partners to collectively focus their direction. As Bruntland stated, “The ‘environment’ does not exist as a sphere separate from human actions, ambitions, and needs, and attempts to defend it in isolation from human concerns have given the very word ‘environment’ a connotation of naivety in some political circles…the ‘environment’ is where we live; and ‘development’ is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable.” Many in practice, including the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), have adopted the three pillars concept. By linking economic, environmental, and social impacts together to understand “development,” even as overlapping as they are, an extremely broad group of specialists and advocates from a variety of nations and cultures were able to see themselves in the work of others for the benefit of society as a whole. Zooming into the program/project level in the built environment, some of the economic impacts have been easy to understand related to employment opportunity and connectivity, real estate values, return on investment (ROI), etc. Environmental impacts can be understood according to land degradation, water pollution, air pollution, etc. To some extent, for lack of better tools for systems analysis, these can be understood with methods that involve looking only at a few variables at a time. For some social issues, the analysis requires a systems thinking approach even for a basic understanding. In a previous blog post, I drafted one way of thinking about the system of repeated cycles of poverty. While we have made significant inroads over the years on understanding environmental and economic impacts, perhaps the reason why we have not made as much progress on social impacts is due to a lack of structured understanding and tools. Until a more level playing field is created for understanding the tradeoffs between economic, environmental, and social impact in the built environment, the analysis will continue to shift in favor of one or the other, even though professionals might acknowledge the importance of all three working in tandem. Democratization of data and data science Making decisions in the complex urban environment is an incredible responsibility. The quality of decision-making is a significant contributing factor to the level of opportunities within a city, and it does influence the lives of the estimated 3.5 billion people living in cities across the world. The democratization of data has made incredible progress in the past several years and continues to do so, but data is only valuable when people know what to do with it. We need what Stephen Wolfram calls a democratization of data science, and for those of us responsible for city decision-making, we need a democratization of urban data science. While it is true that we have incredibly helpful tools such as Geographic Information Systems (even open source versions) and physical city modeling software to guide decisions, these tools do not allow for a simplified analysis of systems and complex/multi-criteria decision-making nor are they accessible to less technical staff and decision makers. They will allow for a few variables to be analyzed at a time while others are generally understood in context, but they do not allow for a system (or system of systems) analysis that encompasses ten or more factors with intricate relationships between each other as explained in a previous blog post. While environmental impact assessments and health impact assessments are critical to moving the three pillars forward and integrating our work, they are time intensive and specialist driven. Due to this, they are not able to scale efficiently to reach professionals who work at every scale of urban development. If more tools and processes could be created to make this type of multifaceted analysis less of a commodity, then there would be more high quality decisions to improve the lives of the 3.5 billion people living in cities. We are now in a data rich world in terms of open data, big data, census data, and others, but how do we structure this data effectively toward the most important decisions we make? Systems leadership Even more than tools and processes, we need people, the kind of people who are “systems leaders.” These are the people who will lead the charge towards integrating data science between silos, disciplines, and subject matter areas for the benefit of those who are most affected by their outputs - the public at large. They understand that high degrees of collaboration are required to achieve results for the public, and they also know that there is a next step in the evolution of how decision-making occurs by working more intentionally as a system. These could be people at high levels of government who oversee various capital programs and budgets that straddle silos. Perhaps they want spending to become more efficient and tied to more focused results. They could be focused agencies/non-profits that tackle certain problems or work on behalf of one target population, but they also realize that their problem is connected to others. They could be real estate developers calibrating return on investment (ROI) with social and environmental concerns important to them as well as the city approving permitting. They could also be private planning firms that assist all these groups with their decision-making. Each group needs tools/processes to better understand how their own work areas and the work areas of related agencies, companies, and non-profits fit together as larger systems. While each city has its nuances and local challenges, the framework of economic, environmental, and social applies to all. There are certain qualities of cities that make them effective, because there are certain qualities of life that make living better for people. In the end, we may be more similar than we realize. People are complex beings. They have different needs and wants and have different situations into which they are born. Around the world, more than 50 percent of people now live in cities. In these urban environments, fully grasping needs and wants is extremely complicated in terms of understanding the tradeoffs between issues such as economic opportunity, transportation access, public health, and many more issues. In order to meet these needs and wants, even in part, a great deal of services are provided and infrastructure is built. The private, public, and nonprofit/philanthropic sectors all provide aspects of the services and infrastructure that is needed. In most nations, the primary responsibility for working on societal level problems is held with the government. Particularly in democratic governments, there is a notion of transparency regarding the tax paying public having access to information about how their tax funds are being spent on various initiatives, in support of specific goals, and making various levels of progress over the years. The needs and wants of people in the urban environment are complex and nuanced, bridging many subject matter areas, while government agencies tend to be structured by separate subject matter areas and tasked with completing specific programs within these areas. Professional success and incentives are often tied to staff members' performance in pursuit of subject matter specific initiatives. People often refer to this is a "siloed" system and even go one step further using a phrase, "breaking down silos," which is generally understood to be cooperating together on joint goals (if not actually restructuring in a less siloed way). In reality, the needs of people are not necessarily subject specific, although they sometimes appear to be. The past Let's go back in time to the 1950's. During this and the following decades, the United States (US) was investing heavily in building the interstate network to connect cities and towns to each other and optimizing local roads within cities and towns for automobile traffic. While the focus during earlier periods was on pedestrian and transit connectivity, the nation experienced a fundamental shift over many decades in transportation strategy and public investment toward auto-centric infrastructure. Many activists were forced to go to great lengths to protect neighborhoods within American cities from interstates (which are primarily intended for connectivity between cities/metro areas, not connectivity within cities/metro areas) slated to divide historic communities in the name of expedient travel. One well-known example is Jane Jacobs' battle with Robert Moses in New York City over this very issue during the 1960's. Jacobs and other supporters were successful in the end, but other American cities such as Atlanta (images below from the Institute for Quality Communities) have long suffered the consequences of interstates that dissected long-standing communities. Across the US, this advocacy for keeping neighborhoods intact at this time was referred to as the "Highway Revolts." The focus on optimizing the nation for the automobile had not only community-level consequences, but also very serious public health consequences that plague American society to this day. Obesity and obesity-related chronic illnesses have grown steadily over the decades. The obesity epidemic is due in part to the reduction of active transportation/transit options and an overall auto-centric environment that requires very little walking (medical prescriptions, banks, fast food, etc. are even available directly from the car, to the occasional shock of non-Americans). The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states, “Obesity is a national epidemic and a major contributor to some of the leading causes of death in the U.S., including heart disease, stroke, diabetes and some types of cancer. We need to change our communities into places that strongly support healthy eating and active living.” Although there are additional factors that have led to the obesity epidemic, our built environment is undoubtedly a significant contributor. The present These chronic illnesses often require continual treatment, as is the case with both Type 2 diabetes and kidney disease/end stage renal disease (ESRD). The CDC states, “The rise in the incidence of Type 2 diabetes cases is associated with increases in obesity, decreases in leisure-time physical activity, and the aging of the U.S. population." The chart below shows that the number of cases of diabetes in the US increased an estimated 280% between 1980-2010, while the population increased by 36.5% during the same period (US Census Bureau). Of total diabetes cases, approximately 95% are Type 2. For kidney disease/end stage renal disease (ESRD), dialysis patients often require treatment around 3 times per week for prolonged periods of time. Patients, sometimes unable to drive themselves due to their post-treatment condition, often rely on public transportation or Medicaid door-to-door transportation. If they do get there by car, it is because they can afford their own vehicle or have a generous support network of family/friends. In the latter case, there are likely feelings of dependency and guilt regarding the drivers’ time, as the trips are very frequent (conflicting with the drivers' work schedules and other obligations). The charts below illustrate the rising incidence of ESRD overall and by race specifically. African Americans and American Indians are significantly more affected than others. Our health problems related to auto-centric infrastructure do not stop at obesity-related illnesses, but they continue to health problems as a result of air pollution. The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) states that cars and trucks number one cause for air pollution in the US. The UCS also says that, in the US, “Particulate matter is singlehandedly responsible for up to 30,000 premature deaths each year.” They also point out that almost one half of all Americans (estimated 150 million) are living in areas which do not meet the air quality standards of the federal government. A study published in 2012 by pollution experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) concluded that air pollution from roads is twice as likely to cause death when compared to traffic accidents in the United Kingdom (UK). Research by the European Commission in 2005 came to similar conclusions regarding premature deaths for all countries in the European Union. In the UK, they have considered strategic action related to building locations, in particular, separating schools and hospitals from roads. Ironically, this solution would potentially require people to drive farther if transit or active transport options (walking, cycling) are not used, contributing to additional pollution. The US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) report, Our Nation’s Air: Status and Trends Through 2010, provides a few graphics (below) to illustrate the impact of air pollution in terms of number of dangerous air quality days per year and cancer risk from air toxics. Transportation is not the only contributing factor to our air quality, but it is documented as one of the most significant. One of the most tragic ways these public health impacts are manifested is in our children’s lives. The rates of childhood obesity have skyrocketed over the years as people have become less and less likely to integrate exercise (even passively through transportation) into their daily routines. Of course, food access and other issues factor into the situation, but the built environment remains a significant contributor. Consequences of framing problems incorrectly The key is this - we saw transportation as a simple problem. We thought it was as simple as getting people where they needed to go, from point A to point B, as fast as possible. In fact, we were incorrect, and the decisions of previous generations have led to children of the present generation having significant health problems. We simply solved one problem (as we narrowly defined it) and created a few more in its wake as a result of limited thinking and incorrect problem framing. We suffer dire consequences; these health issues will follow our children as adults and significantly reduce their quality of life. We, at least those of us who live in a democratic society, are responsible. We are responsible for not holding our governments accountable for decisions that will greatly impact lives in current and future generations. We are responsible for not being careful with our own money, our tax money, which is pooled to make these investments. We are all held accountable for responsible decision making. The (hopefully different) future We are now living in an era in which we have the technology to avoid some unintended consequences and treat urban problems in their full complexity. We can summarize this information clearly to communicate effectively with the public. We have the open data, the big data, the crowd sourced data and the data models to structure and make sense of relationships. We have skilled experts on subject matter areas who understand interconnectivity between problems. We have people who have lived in their communities for decades and know its present and future needs. We can set up new systems for accountability, transparency, and clear communication. We only need to decide that it is a priority, create new infrastructure, and use it. "What’s worse, there is no overarching authority that is formally charged with bringing these disparate data sets together and constructing a model for identifying the true picture..." In the article, Building a Government Data Culture, Mark Headd talks about understanding the multifaceted issue of vacant properties in Philadelphia and general issues of government disconnect. It is a well-known problem that issues falling between government divisions, between government agencies, and between nonprofit and government organizations are often not dealt with effectively. Unfortunately, some of the most significant, systemic, and intractable problems fall into this area. Poverty is one such problem. For example, one aspect of poverty is having access to the right work opportunities, but it starts many years before a person seeks their first job and involves many additional factors. It straddles economic development, housing, transportation, food access, early childhood education, workforce development, and even more subject matter areas. Some US cities have no one entity that coordinates a structured response to poverty, even as our poverty levels rise to new heights. Strategic refocusing Restructuring government offices is one option, but strategically refocusing is another. Strategic refocusing entails aligning work according to problems and solutions, not according to the department/division on based labor division and professional specialty areas. The good news is that strategic refocusing, if adopted, could be a clear process with simple steps. It would mainly involve professionals changing the lens through which they look. At the heart of breaking down silos is collaborative decision-making through specific tools and processes. There is no appropriate solution without deep understanding of a problem and its root causes. First, the most challenging problems facing a given geographic area (city, county, metro area, state, etc.) would be defined to set the scope. These would not be goals, as goals are actually solutions and are often decided prematurely based on limited information. Goals arrived at too early are often an attempt to oversimplify what is not simple. As explained in the poverty example above, the most significant problems exist in-between subject specific areas. Other examples include traffic congestion, environmental degradation, and countless others. Subject matter experts, community members, and other stakeholders with a deep knowledge of local conditions would work to structure the problems, eventually creating “problem constellations” such as this one for repeated cycles of poverty. The red rectangle contains the identified problem, while the orange ellipses contain subject matter areas likely to fall within the purview of one organization or another. Once there is relative agreement on each problem constellation, work would begin on linking these together for a complete “problem picture.” That picture would look something like the one below. The detail of the repeated cycles of poverty problem constellation was simplified for the sake of the graphic (but the actual analysis would not be). Again, red rectangles depict identified problems, while orange ellipses depict subject matter areas. Dashed lines are used when two issues are far apart on the graphic, yet significantly related. Examples have been provided for the sake of illustration; they do not represent undeniable facts. For each problem, with each group of people, outcomes would differ significantly. The process of creating this graphic is a great benefit in that it forces a discussion on what the real needs are and takes into account nuances. The graphic, as a product of the process, also provides a tool to go back and continue the discussion as situations change. The problem picture actually freezes the problems at a point in time, making something very fluid in reality static for the purpose of detailed analysis. Once the structure of the problems is set, work begins on identifying data sources and connecting the data to a model with the problem structure. Some data will be easily available, while some won't be. One additional step is to identify this missing data in order to pinpoint/create it in later phases of development. Once data are available, they are connected to model points/nodes where relevant. A lower tech method (more manual process) can be used until a higher tech one is available. For examples of data sets related to the illustrations above, feel free to contact the author (excluded due to level of detail, but open for sharing).

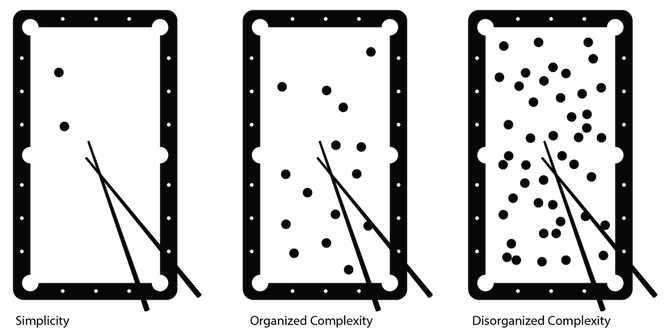

Pinpoint needed results, then tactics Once the problems are understood, work can begin on solutions. In some fields, this would be called options or alternatives analysis. Solutions can be understood as two-fold - tactics and results. Tactics are the programs and infrastructure put in place to alleviate problems, while results are the intended effects of the tactics. In some fields, there is no clear delineation between the two, which is a serious gap. Some professionals have become overly focused on tactics (often making assumptions about their effects/results). It is always best to focus first on the result, and allow the tactics to be the means to the end (they are rarely the end itself). Take transportation for example - the needed result, in broad sense, is connectivity between critical places for people. For this result, transportation infrastructure/services and strategic location of facilities, homes, etc. both come into play as equal tactics, since both approaches help achieve the same result of connectivity. Once a list of draft results and related tactics has been created with a group of professionals and stakeholders, testing can be begin. By systematically comparing the results against the problem areas, a group can see how well the results could help solve the problem. Once the needed results have been finalized and prioritized, the tactics get more attention. As tactics are decided to be an appropriate fit, indicators are created for how their performance (tied to results) will be measured. How will each tactic, in combination with other tactics, achieve the anticipated results? It is not important that each step is perfect or completely correct (in fact, that would be impossible), but it will become a baseline for action and sets the tone for recalibration as the data is monitored over time. In the end, the ability of the selected tactics to reach the results might not be the perfect solution, but the monitoring data will inform recalibration over time. Tactics would actually change over time as data reveals what is working toward the results most effectively. Scenario analysis, the combination of various tactic/result sets, is also an option and might make the process easier for a large group. Comprehensiveness first, then separate parts As the process moves forward, a set of measured tactics and results would have been developed with the group as a comprehensive solution to combat the problem. These tactics would then feed into individual work plans, programs, strategic plans, etc. of the various organizations. They could communicate the holistic goals or keep to their own subject matter area. Sometimes the latter is required to keep in compliance with federal regulations. It is possible to have a comprehensive and holistic approach to solving joint problems while also dividing the solutions into component parts for the sake of keeping track of subject matter area progress. This holds individual organizations accountable for their part only while working more effectively on broad societal needs. Structured public communication What may have been chaotic in the past can actually be quite systematic and structured in the future. Structured processes have the added benefit of enabling clear communication with diverse audiences. At any point, this information could be provided to the public. Of course, each audience is different, and it could be more effective illustrate a simplified or tailored version. Demonstrating progress "Each is stuck in a pattern of looking only at their own data. There are no incentives for these agencies to combine data or cross check it against the data of other departments that might have insight into the problem... Since there isn’t a clear picture of the problem of vacancy, how do we know if we’re making progress in addressing it?" Headd asks a critical, yet often unaddressed, question. We need an evidence-based 360° analytical and action framework to reduce unintended consequences and to allow for recalibrating our approach with data month-by-month and year-by-year. Do we want to look back in 50 years and see eras of misguided decisions upon other eras of misguided decisions? Being successful at handling the complexity of people requires deciding that our future will be different than our past. “Think of it. We are blessed with technology that would be indescribable to our forefathers. We have the wherewithal, the know-it-all to feed everybody, clothe everybody, and give every human on Earth a chance. We know now what we could never have known before -- that we now have the option for all humanity to make it successfully on this planet in this lifetime. Whether it is to be Utopia or Oblivion will be a touch-and-go relay race right up to the final moment” (Fuller, 1981). R. Buckminster Fuller realized the capacity for urban problem solving in the 1970’s, and in the present time, the challenges he refers to have continued to grow dramatically in scale. People move to cities for the promise of the city. This promise is multi-faceted, including diverse job options, quality education, encounters with people, culture and activities, and much more. It is a place where one can rise beyond their previous circumstances and recreate themselves. Cites should have limitless opportunities and possibilities for those with imagination and determination. Historically, cities have been this beacon for many across the world. In our present times, we need to ask ourselves if we believe in this vision, this promise. Do we work to reinstate this promise? What kind of problem is a city? In Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs said, “…one of the main things to know is what kind of problem cities pose, for all problems cannot be thought about in the same way” (Jacobs, 1961). She went on to explain the three known problem types in the physical sciences and how to consider them in the context of cities: 1) simplicity, 2) disorganized complexity, and 3) organized complexity. Simplicity deals with problems in the natural world that comprise a few variables (often expressed as equations), while disorganized complexity contains potentially thousands of variables (often expressed as statistical measurements). Dr. Warren Weaver, whose work in the natural sciences Jacobs’ was referencing in the book, explained that organized complexity is comprised of a number of factors (somewhere between 2-3 and thousands), and can be imagined as a billiards table. If there are only a few balls, it is easy to understand the causal relationships. When there are, say, 15 balls, it can become very difficult to understand the relationships between actions. Here is a diagram to illustrate the 3 problem types: In the same book, Jacobs wrote “…and so a growing number of people have begun, gradually, to think of cities as problems in organized complexity--organisms that are replete with unexamined, but obviously intricately interconnected, and surely understandable, relationships… As long as [we] cling to the unexamined assumptions that [we] are dealing with a problem in the physical sciences [that is, of mechanics], city planning cannot possibly progress…it has found the shortest distance to a dead end” (Jacobs, 1961). Can these complex issues be understood abstractly as interconnected and overlapping factors? Here is a diagram to visualize abstract relationships of organized complexity: Systemic issues such as poverty illustrate the need to think comprehensively. We know the root causes of poverty are complex and touch many aspects of home life as well as services and infrastructure. If we were to draw as a web type diagram to illustrate, we’d see intersecting factors including early childhood education, food security, economic opportunity, affordable housing, transportation, and many more factors. We would also see that these root causes would lead to other results, overlapping with crime, fractured communities, feelings of hopelessness, and more. Members of the public who live this daily and generational experience would be needed to truly grasp the nuances of connectivity, and professional specialists would have a great deal to offer. Here is a diagram to illustrate a draft concept of how groups of people might collaborate on the specifics of a particular problem and its root causes (actual factors are provided only as an illustration by the author, they are not intended as fact): Who works on city improvements?

Over many decades, the work of improving cities has been divided up to make sense of our world, and to our credit, we've successfully made some sense of it. There are people who work on built aspects (such as engineers), natural aspects (often specialized in environmental planning), and the “unseen” or more abstract elements that make cities function for people. The last is the most difficult to explain, and many would not agree on where it starts and ends. For the sake of discussion, let’s have a broad understanding encompassing things like education, job access, senior services, food availability, health and wellness services, and many more. The people working on it directly are as diverse as all the areas it encompasses. It seems that within each person’s path to succeed, we focus on the immediate task at hand. Sometimes, that immediate task is challenging all by itself. It is understandable that many are not able to even identify, much less act on, the type of interconnectivity needed to foster the flourishing of cities. In general, most of us focus on a specialty area (such as economic development, transportation, land use, etc.), and we are assessed based on our subject-matter expertise and ability to make improvements within this realm. Rewards and incentives, including career progression, income, and status, center on our performance within our specialty areas. Having specialists on subject matter areas is critical, and it is important that we understand certain areas deeply. However, in this era of specialists, it is more important then ever to have people who understand the connective tissue between all of the specialty areas in a very deep and meaningful way. The field of urban improvements, which includes many professionals such as urban planners, engineers, community leaders, technologists, etc., lacks key figures who are the connectors. While there is more and more theory being published related urban development’s relationship with complexity science and systems engineering, with many practitioners finding the points to be completely logical, even obvious, there is little action taking place on a large scale to gradually transform the way our cities are developed accordingly. Some notable authors on the topic include Michael Batty, Luís M. A. Bettencourt, Steven Johnson, and T. Irene Sanders, among others. If practitioners were to agree these changes are needed, we would also agree that specific people, training/education, processes, and low-high tech tools to facilitate the change are needed. How can we work to reinstate the promise of cities? Do we have the “wherewithal, the know-it-all” to work towards such lofty goals? If yes, are those of us professionally focused on urban improvements positioned strategically enough to make progress? It depends on our understanding of small to large-scale improvements and how they can be approached strategically. If we don’t work towards a shift in thinking and action, we’ll continue to not see the forest for the trees (or not see the larger promise of the city for the small components). Unless we are extremely clear about what it is we set out to accomplish and measure progress accordingly, it is not possible to know our true impact. Cities are complex organisms to be sure, and one, understandably, might focus day to day without understanding their system-wide impact and personal contribution over the years. The final moment has not come yet. While we might not end at “Utopia or Oblivion” exactly, we can actively work towards one end of the spectrum or the other. How are we directing our contribution? Works Citied Fuller, R. Buckminster. Critical Path. St. Martin's Griffin, 1981. Jacobs, Jane. Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961. |

Archives

September 2015

AuthorJanae Futrell, Purpose

Structuring urban change while taking into account complexity, communication, and transparency Please Note

All views, posts, and opinions shared are my own. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed