|

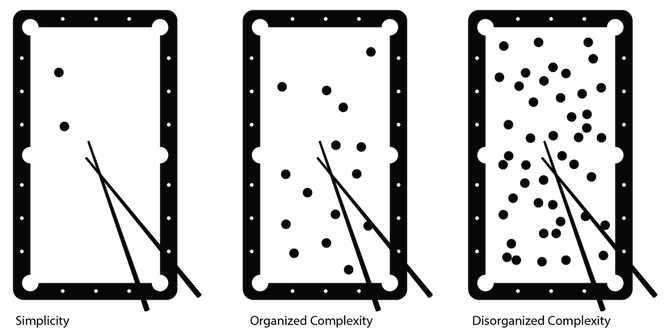

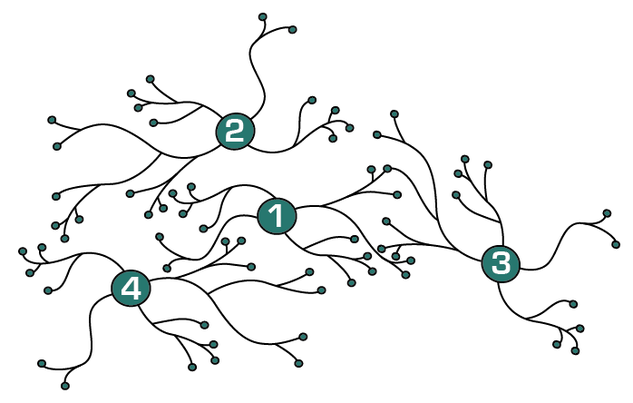

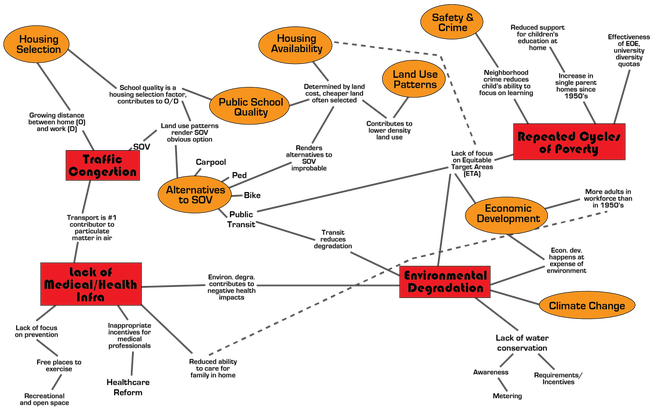

“Think of it. We are blessed with technology that would be indescribable to our forefathers. We have the wherewithal, the know-it-all to feed everybody, clothe everybody, and give every human on Earth a chance. We know now what we could never have known before -- that we now have the option for all humanity to make it successfully on this planet in this lifetime. Whether it is to be Utopia or Oblivion will be a touch-and-go relay race right up to the final moment” (Fuller, 1981). R. Buckminster Fuller realized the capacity for urban problem solving in the 1970’s, and in the present time, the challenges he refers to have continued to grow dramatically in scale. People move to cities for the promise of the city. This promise is multi-faceted, including diverse job options, quality education, encounters with people, culture and activities, and much more. It is a place where one can rise beyond their previous circumstances and recreate themselves. Cites should have limitless opportunities and possibilities for those with imagination and determination. Historically, cities have been this beacon for many across the world. In our present times, we need to ask ourselves if we believe in this vision, this promise. Do we work to reinstate this promise? What kind of problem is a city? In Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs said, “…one of the main things to know is what kind of problem cities pose, for all problems cannot be thought about in the same way” (Jacobs, 1961). She went on to explain the three known problem types in the physical sciences and how to consider them in the context of cities: 1) simplicity, 2) disorganized complexity, and 3) organized complexity. Simplicity deals with problems in the natural world that comprise a few variables (often expressed as equations), while disorganized complexity contains potentially thousands of variables (often expressed as statistical measurements). Dr. Warren Weaver, whose work in the natural sciences Jacobs’ was referencing in the book, explained that organized complexity is comprised of a number of factors (somewhere between 2-3 and thousands), and can be imagined as a billiards table. If there are only a few balls, it is easy to understand the causal relationships. When there are, say, 15 balls, it can become very difficult to understand the relationships between actions. Here is a diagram to illustrate the 3 problem types: In the same book, Jacobs wrote “…and so a growing number of people have begun, gradually, to think of cities as problems in organized complexity--organisms that are replete with unexamined, but obviously intricately interconnected, and surely understandable, relationships… As long as [we] cling to the unexamined assumptions that [we] are dealing with a problem in the physical sciences [that is, of mechanics], city planning cannot possibly progress…it has found the shortest distance to a dead end” (Jacobs, 1961). Can these complex issues be understood abstractly as interconnected and overlapping factors? Here is a diagram to visualize abstract relationships of organized complexity: Systemic issues such as poverty illustrate the need to think comprehensively. We know the root causes of poverty are complex and touch many aspects of home life as well as services and infrastructure. If we were to draw as a web type diagram to illustrate, we’d see intersecting factors including early childhood education, food security, economic opportunity, affordable housing, transportation, and many more factors. We would also see that these root causes would lead to other results, overlapping with crime, fractured communities, feelings of hopelessness, and more. Members of the public who live this daily and generational experience would be needed to truly grasp the nuances of connectivity, and professional specialists would have a great deal to offer. Here is a diagram to illustrate a draft concept of how groups of people might collaborate on the specifics of a particular problem and its root causes (actual factors are provided only as an illustration by the author, they are not intended as fact): Who works on city improvements?

Over many decades, the work of improving cities has been divided up to make sense of our world, and to our credit, we've successfully made some sense of it. There are people who work on built aspects (such as engineers), natural aspects (often specialized in environmental planning), and the “unseen” or more abstract elements that make cities function for people. The last is the most difficult to explain, and many would not agree on where it starts and ends. For the sake of discussion, let’s have a broad understanding encompassing things like education, job access, senior services, food availability, health and wellness services, and many more. The people working on it directly are as diverse as all the areas it encompasses. It seems that within each person’s path to succeed, we focus on the immediate task at hand. Sometimes, that immediate task is challenging all by itself. It is understandable that many are not able to even identify, much less act on, the type of interconnectivity needed to foster the flourishing of cities. In general, most of us focus on a specialty area (such as economic development, transportation, land use, etc.), and we are assessed based on our subject-matter expertise and ability to make improvements within this realm. Rewards and incentives, including career progression, income, and status, center on our performance within our specialty areas. Having specialists on subject matter areas is critical, and it is important that we understand certain areas deeply. However, in this era of specialists, it is more important then ever to have people who understand the connective tissue between all of the specialty areas in a very deep and meaningful way. The field of urban improvements, which includes many professionals such as urban planners, engineers, community leaders, technologists, etc., lacks key figures who are the connectors. While there is more and more theory being published related urban development’s relationship with complexity science and systems engineering, with many practitioners finding the points to be completely logical, even obvious, there is little action taking place on a large scale to gradually transform the way our cities are developed accordingly. Some notable authors on the topic include Michael Batty, Luís M. A. Bettencourt, Steven Johnson, and T. Irene Sanders, among others. If practitioners were to agree these changes are needed, we would also agree that specific people, training/education, processes, and low-high tech tools to facilitate the change are needed. How can we work to reinstate the promise of cities? Do we have the “wherewithal, the know-it-all” to work towards such lofty goals? If yes, are those of us professionally focused on urban improvements positioned strategically enough to make progress? It depends on our understanding of small to large-scale improvements and how they can be approached strategically. If we don’t work towards a shift in thinking and action, we’ll continue to not see the forest for the trees (or not see the larger promise of the city for the small components). Unless we are extremely clear about what it is we set out to accomplish and measure progress accordingly, it is not possible to know our true impact. Cities are complex organisms to be sure, and one, understandably, might focus day to day without understanding their system-wide impact and personal contribution over the years. The final moment has not come yet. While we might not end at “Utopia or Oblivion” exactly, we can actively work towards one end of the spectrum or the other. How are we directing our contribution? Works Citied Fuller, R. Buckminster. Critical Path. St. Martin's Griffin, 1981. Jacobs, Jane. Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961. |

Archives

September 2015

AuthorJanae Futrell, Purpose

Structuring urban change while taking into account complexity, communication, and transparency Please Note

All views, posts, and opinions shared are my own. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed